This store requires javascript to be enabled for some features to work correctly.

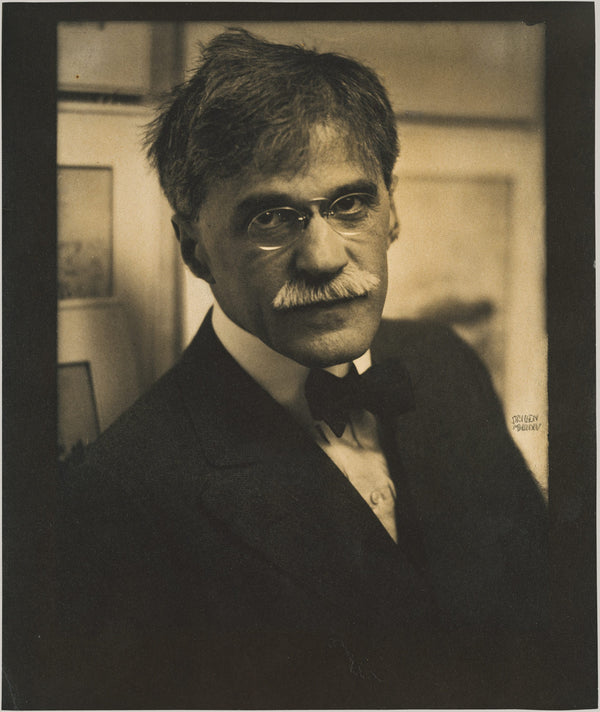

Alfred Stieglitz

One can’t deny the impact of Alfred Stieglitz in the development of modern American art—not only due to his own photography, but also his work as an art dealer, gallerist, publisher, and promoter of other artists. The rise of modern photography owes a great debt to his drive and determination: Stieglitz made it his mission to cement photography as an artistic medium.

Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1864, but grew up in Germany. He purchased his first camera in 1882, creating images of the countryside and researching more about the medium. In 1890, he moved back to America and settled in New York City. He solidified his position in the still small world of photography with stints working for The American Amateur Photographer and launching Camera Work.

Friend and fellow photographer Edward Steichen encouraged Stieglitz to open an exhibition space, which he did, calling it the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession. It was the first gallery to hold paintings and photographs to the same aesthetic status. The gallery—later known as 291—exhibited both Stieglitz’s work and the art of American and European modernists, becoming the hot spot for promoting new artists and exploring philosophical views in the arts. It was through this gallery that Stieglitz met his muse, the American painter Georgia O’Keeffe. He was so taken with her work that he displayed it in Gallery 291 without her permission; when they first met, it was so she could chastise him. Their relationship began shortly after and informed much of his oeuvre.

Though photography was still developing as an artistic medium in Stieglitz’s working years, he insisted on taking it to its limits. By the 1920s, he had accomplished much of what was said to be impossible with photo-chemistry: photographing at night, in low light, in bad weather, and in color. He also pushed artistic limits by creating some of the first abstract photographs, making a series of nudes, and developing the idea for a composite portrait. Stieglitz felt that in order for photography to be recognized as an art form, it had to push its own boundaries beyond technical skill into the realm of truly impactful visual appeal. Though he died in 1946, his work stands the test of time and continues to inform modern day photography.

Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1864, but grew up in Germany. He purchased his first camera in 1882, creating images of the countryside and researching more about the medium. In 1890, he moved back to America and settled in New York City. He solidified his position in the still small world of photography with stints working for The American Amateur Photographer and launching Camera Work.

Friend and fellow photographer Edward Steichen encouraged Stieglitz to open an exhibition space, which he did, calling it the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession. It was the first gallery to hold paintings and photographs to the same aesthetic status. The gallery—later known as 291—exhibited both Stieglitz’s work and the art of American and European modernists, becoming the hot spot for promoting new artists and exploring philosophical views in the arts. It was through this gallery that Stieglitz met his muse, the American painter Georgia O’Keeffe. He was so taken with her work that he displayed it in Gallery 291 without her permission; when they first met, it was so she could chastise him. Their relationship began shortly after and informed much of his oeuvre.

Though photography was still developing as an artistic medium in Stieglitz’s working years, he insisted on taking it to its limits. By the 1920s, he had accomplished much of what was said to be impossible with photo-chemistry: photographing at night, in low light, in bad weather, and in color. He also pushed artistic limits by creating some of the first abstract photographs, making a series of nudes, and developing the idea for a composite portrait. Stieglitz felt that in order for photography to be recognized as an art form, it had to push its own boundaries beyond technical skill into the realm of truly impactful visual appeal. Though he died in 1946, his work stands the test of time and continues to inform modern day photography.