Plate 250: Arctic Tern by John James Audubon 10"x8" ($24) | 14"x11" ($60) | 20"x16" ($240) | 30"x24" ($800) |

Plate 431: American Flamingo by John James Audubon 10"x8" ($24) | 14"x11" ($60) | 20"x16" ($240) | 30"x24" ($800) |

You might be wondering: why feature two completely different birds together on this double Audubon release day? One is swooping gracefully toward the water, feathers aligned with the precision of a dive bomber. The other bird is brightly-hued and bends its long, contortionist’s neck towards the shore, its spindly legs pointed peculiarly backward. One reminds us of stormy seas and hazy gray mornings, while the other calls to mind humid days and tropical flowers. Here is your answer: what makes these two individual birds so incredible together is that they represent range.

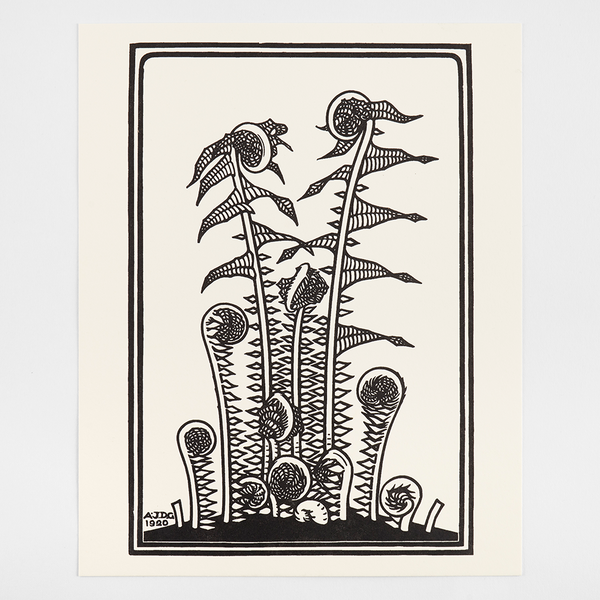

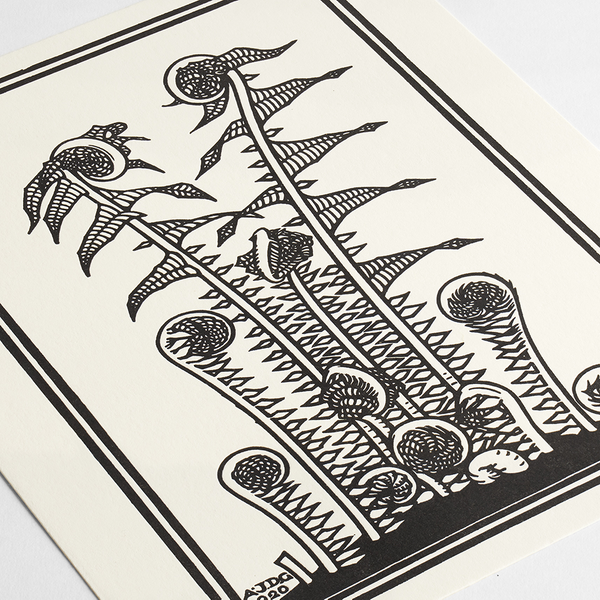

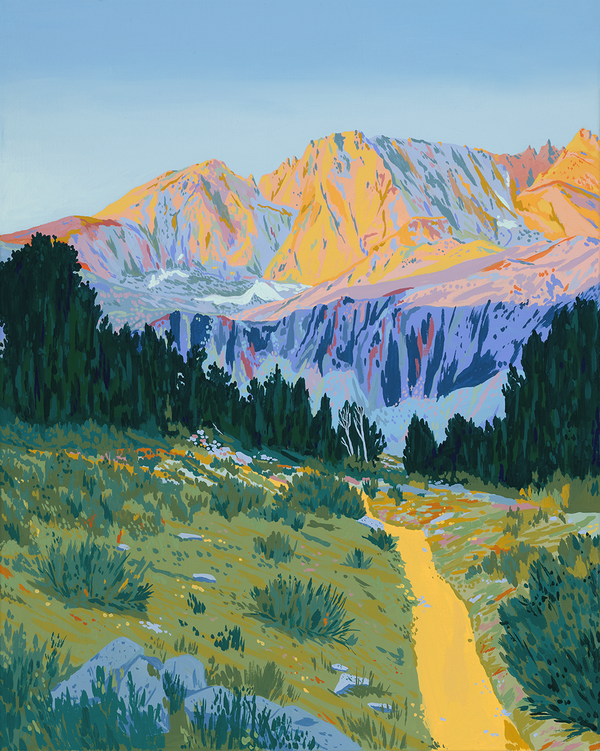

Plate 431: American Flamingo by John James Audubon

These two birds are utterly unalike—Plate 250: Arctic Tern and Plate 341: American Flamingo—and yet they are both part of John James Audubon’s seminal work, Birds of America. That’s right: two completely different birds from very different areas of the country can still be termed under the catch-all term “American”. What a perfect metaphor for this melting pot we call home?We’re grateful for the reminder—in the form of Audubon’s art—that “American” is no singular identity, but rather a beautiful amalgamation of many distinct ones.

Plate 250: Arctic Tern by John James Audubon

And certainly, America needs people like John James Audubon. Despite not being born on this side of the Atlantic, he saw more of North America than anyone alive, eventually coming to symbolize its wilderness. Talented though he was, to call the man an artist alone would be dismissive of the progressive work he did in the ornithological and naturalist communities. A self-taught scientist, Audubon conducted several innovative experiments that led to the first recorded instance of banding birds. He applied this same mind to his art and his travels, leading him to the far reaches of the continent to capture both the Arctic tern and the American flamingo, at opposite ends of the avian spectrum.

We consider ourselves lucky to be able to study the art of John James Audubon, and to use that study as an impetus to learn more about the past of America’s wilds, as well as its continued future. From what little we know, it seems pretty clear: in order to be great, America needs all kinds—of birds, of minds, and of art.

With art for everyone,

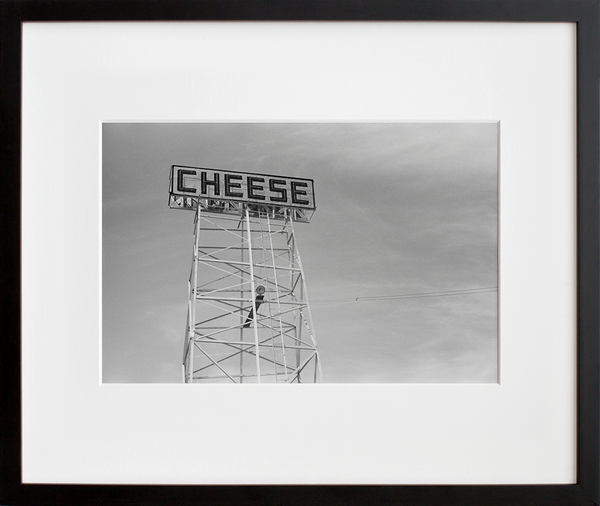

Jen Bekman + Team 20x200