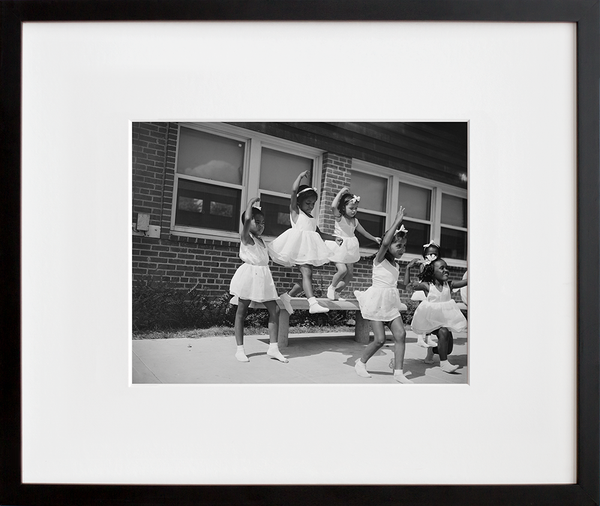

We have three tales for thee: some 18th century drama, some 20th century drama, and the foraging tradition of a matriarchal society. Read on!

The "sea women" of South Korea are seemingly superhuman.

© Haenyeo Museum, 2005 and 2012 via UNESCO

Haenyo, literally meaning “sea women”, are the female deep-sea divers of Jeju-do, South Korea. They live a dual lifestyle—one belonging to the land and the other to the sea. It is easy to see how the myth of the mermaid was born as you watch the Haenyo surface from the deep and communicate with songs and whistles. With mermaid statues scattered throughout the coast of this island, it’s clear that these women are upholding a tradition as well as supporting a myth.

Haenyo perform perilous work to provide for their families, spending five hours a day diving in rubber suits, without air tanks as the law requires, to collect valuable sea life attached to the bottom of the ocean floor. They develop what is referred to as Muljil skill, acquired by lengthy training and experience, and can hold their breath for more than three minutes and dive to depths of thirty meters. Because tradition dictates that only women dive, the Haenyo have created a matriarchal society on the island that differs greatly from the patriarchal one on the mainland of South Korea.

Today, the number of Haenyo is declining drastically and its tradition is in danger of extinction as fewer women are choosing it as a profession due to better opportunities and industrialization. Haenyo Emerging for Air is part of Ian Baguskas’s series, shot using 4x5 and 6x7 film cameras, that documents this dying tradition.

Painter "prostitutes his own wife" to create a masterpiece.

François Boucher (1703-1770), a prolific French painter, draftsman and etcher, came under harsh criticism towards the end of his career when his work was labeled as trivial, decorative, and at times erotic. This dark-haired version of the L'Odalisque portraits prompted claims by the art critic Denis Diderot that Boucher was "prostituting his own wife". In his Salon 1767 Diderot denounced this shocking image of a “woman completely nude lying on pillows, legs here, legs there, poised for pleasure." We censored the image in this email because, 260 years later, we have cause to worry that showing a woman’s naked booty in an email will come back to bite us in the butt, so to speak. But if you think you can handle the full image, continue on to our site.

Spite (in part) led to the creation and popularization of a new genre of art.

Did you know that abstract fine art photography as a genre was partially created and popularized out of spite? It’s true. In 1922, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, best known for his artistic partnership with Georgia O’Keefe, received some comments on his work from novelist and literary critic Waldo Frank that really ticked him off. Frank was of the opinion that Steiglitz’s pieces were only successful because of the power of the subjects he photographed, not because of any technical ability on the artist’s part. Outraged, Stieglitz began photographing clouds, something everyone could see but no one could manipulate–his way of proving his artistic prowess. This series was called Equivalents.

At the time Steiglitz created this series, the art world struggled to see photography, not yet a century old, as an artistic medium in its own right. Equivalents is recognized as some of the first completely abstract fine-art photography. Some pieces in the Equivalents series featured more than clouds, or didn’t include clouds at all. In Rain Drops (alternatively titled Equivalent (Rain drops on grass, Lake George), 1927), the patterns of shape and light created by long stalks of grass covered in water droplets pushes the image towards total abstraction.

Lake George, New York, where this piece was photographed, was the location of his summer home and the fertile ground from which his greatest artistic achievements grew. From O’Keefe to grasses, from clouds to poplar trees, from the deathly still to the vibrantly mid-motion, Steiglitz’s Lake George work remained stunningly distinct from and of a different character than the rest of his Manhattan-based photography.