Depending on how long you've been on this planet and where you grew up, you may or may not have had a youth where physical play—largely occurring outdoors—made up the bulk of your fun time. It is mournful that each passing generation of Americans has spent, by and large, less and less time outside with each other IRL; technology has instead captured everyone's attention. Of course, screens simply weren't part of family households in the early 20th Century, and the rippling effects of both the Great Depression and World War II had a huge impact on kids' play.

Stickball and baseball! Sitting outside with your neighbors in giant multi-family gatherings! Archery! Bugle-honking! Bicycle rides with friends! All of these activities, along with playing jacks, marbles and cards were routine parts of many kids' lives 90 years ago. Okay, maybe the bugle-honking was a more niche experience, but you know what we mean. Were these types of leisure activities better, or were they just different? Opinions differ, but one thing's for sure: these images each capture a specificity of time and place that both evokes nostalgia and provide us a window into history.

Inclusive 1940s summer camps

Camp Fern Rock (archer) (left) and Camp Nathan Hale (mess call) (right) by Gordon Parks

Shot by Gordon Parks in the summer of 1943, these images of rare interracial summer camps are reminders that the outdoors belongs to everyone, and that equality in the American wilderness is (quite literally) a beautiful thing.

When Parks photographed seemingly mundane scenes of children of all sorts of races carrying on with assorted camper activities, he overturned the implicitly racist imagery often associated with outdoor recreation and the American wilderness. In his photos, children share meals, swim together, and spend time in nature together, activities that mirror the settings of some of the most antagonistic racial unrest of the time. Caught mid-bugle call against the background of an American flag, the boy in Camp Nathan Hale (mess hall) seems to herald a new era.

At Camp Fern Rock, camper Loretta Gyles aims her arrow out of shot with captivating composure. There’s so much strength in that fist in the fore, so much grace in her angled elbow. Parks’ shallow depth of field blurs the background, emphasizing Gyles against a rapt audience of trees (subverting the racially-charged, violent symbolism of trees in the process). She’s just a girl, but the low angle of the shot gives her a goddess-like presence — Diana the Huntress of upstate NY.

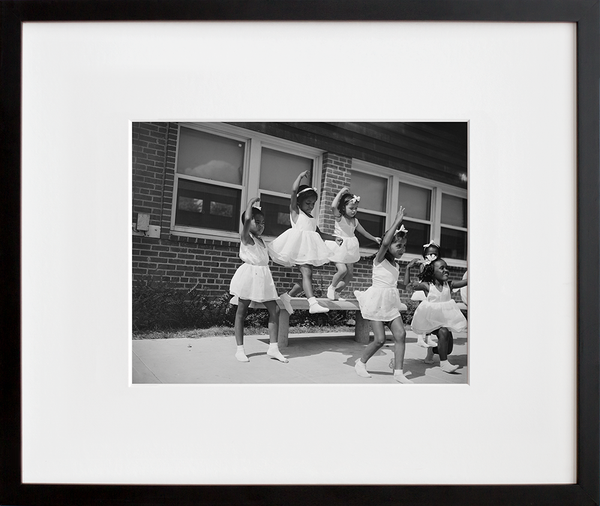

Depictions of joy

Harlem Tenement in Summer, a 20x200 Vintage Edition

The unknown photographer of this image, taken sometime between 1935 and 1939, has chosen to immortalize a quotidian stoop scene. While the youngest Harlemites are at play on the sidewalk or clustered together on the stoop, the adults are mid-conversation, some leaning confidently out of wide open windows above to share a word. This image boasts an openness and camaraderie that implores viewers to linger on every face, challenging us to try to connect the dots between the scene’s many characters.

At a time of such socio-political upheaval, to consider this scene worthy of documentation is a celebration of the historically denied humanity of Black Americans. Throughout the 19th and much of the early 20th century, photography had been used to represent subjects of color as objects of study, and the ethnographic images were tools for justifying the continuation of racial stereotyping. While we don’t know the photographer’s intentions behind Harlem Tenement in Summer, we can note that there is a significant and willing shift in perspective.

Passing time on the home front

Marjory Collins gives us a rare glimpse into life on the home front during World War II. This image evokes a lingering nostalgia for the simplicity of youth gone by, and calls to mind lazy, languid summer days. It also provides a curious juxtaposition between the tranquility of the scene set before us and the brutality of a war raging across the Atlantic; the boys in the photo watch toy sailboats pass by as warships patrol the coasts. The particular magic of this photograph is that despite the rather sobering historical context surrounding it, Collins was able to create an image that fills the viewer with a wave of tranquility. You can almost feel the calm, warm wind that once blew through these willow branches.

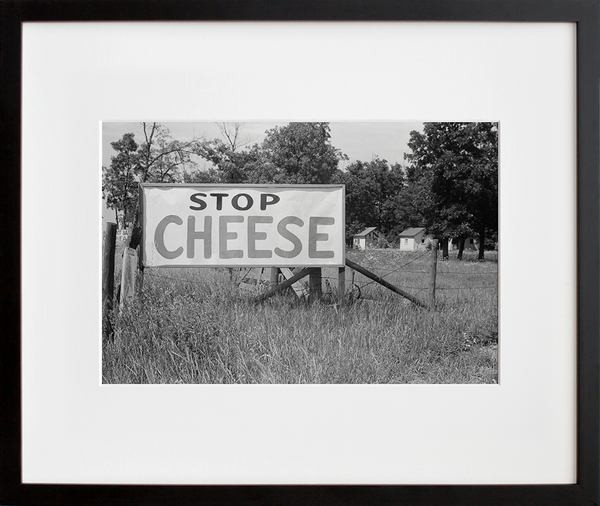

Play in a 1940s rural community bolstered by the New Deal

On an unusually warm day in December of 1941, Farm Security Administration photographer Arthur Rothstein stumbled upon a baseball game. The co-ed game was being played on the grounds of the new Homestead School in Dailey, West Virginia. Funding for the school came through the government in the form of the Resettlement Administration (RA). Part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, the RA helped struggling workers find new homes and jobs in sustainable industries. Dailey was one of three communities brought together into the Tygart Valley Homesteads Historic District in 1934.